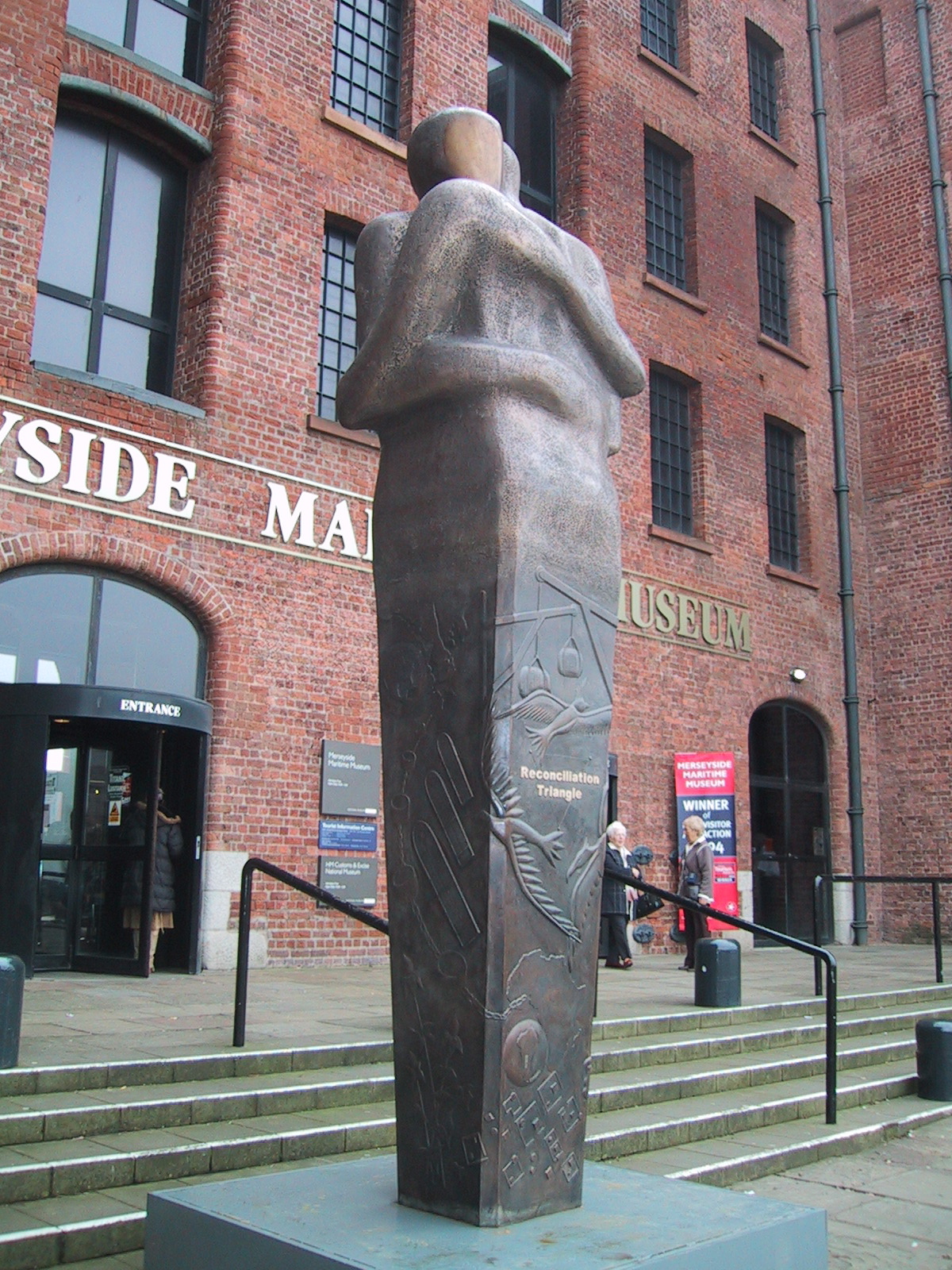

RECONCILIATION TRIANGLE

NAME : Reconciliation Triangle DATE : 1989, 2005 & 2009 CLIENT : Republic of Benin Government, Mayor's Office, City of Richmond, Virginia, Liverpool City Council LOCATION : Liverpool, Richmond Virginia, Benin Africa PARTNERS : Leander Foundry, Reconciliation Trust,

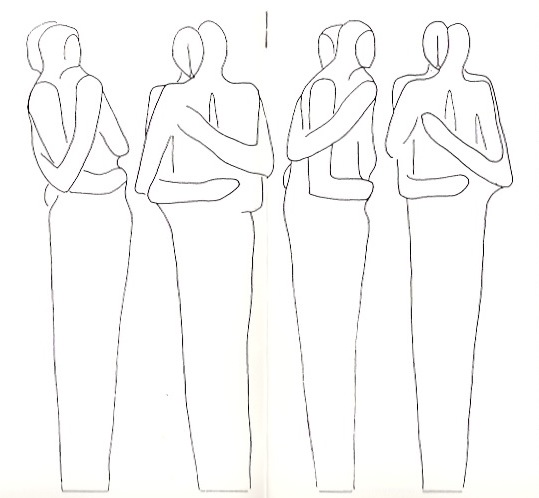

The original Iron Reconciliation sculptures, erected in 1989 in Liverpool, Glasgow and Belfast are a powerful symbol of the way in which sectarianism can be overcome through the solidarity and youth of these three great cities on the Irish sea. See Reconciliation Project

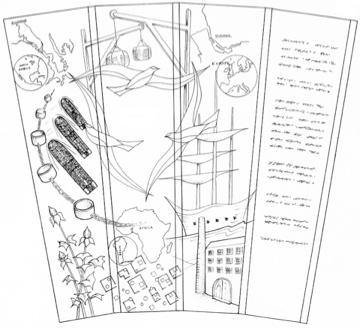

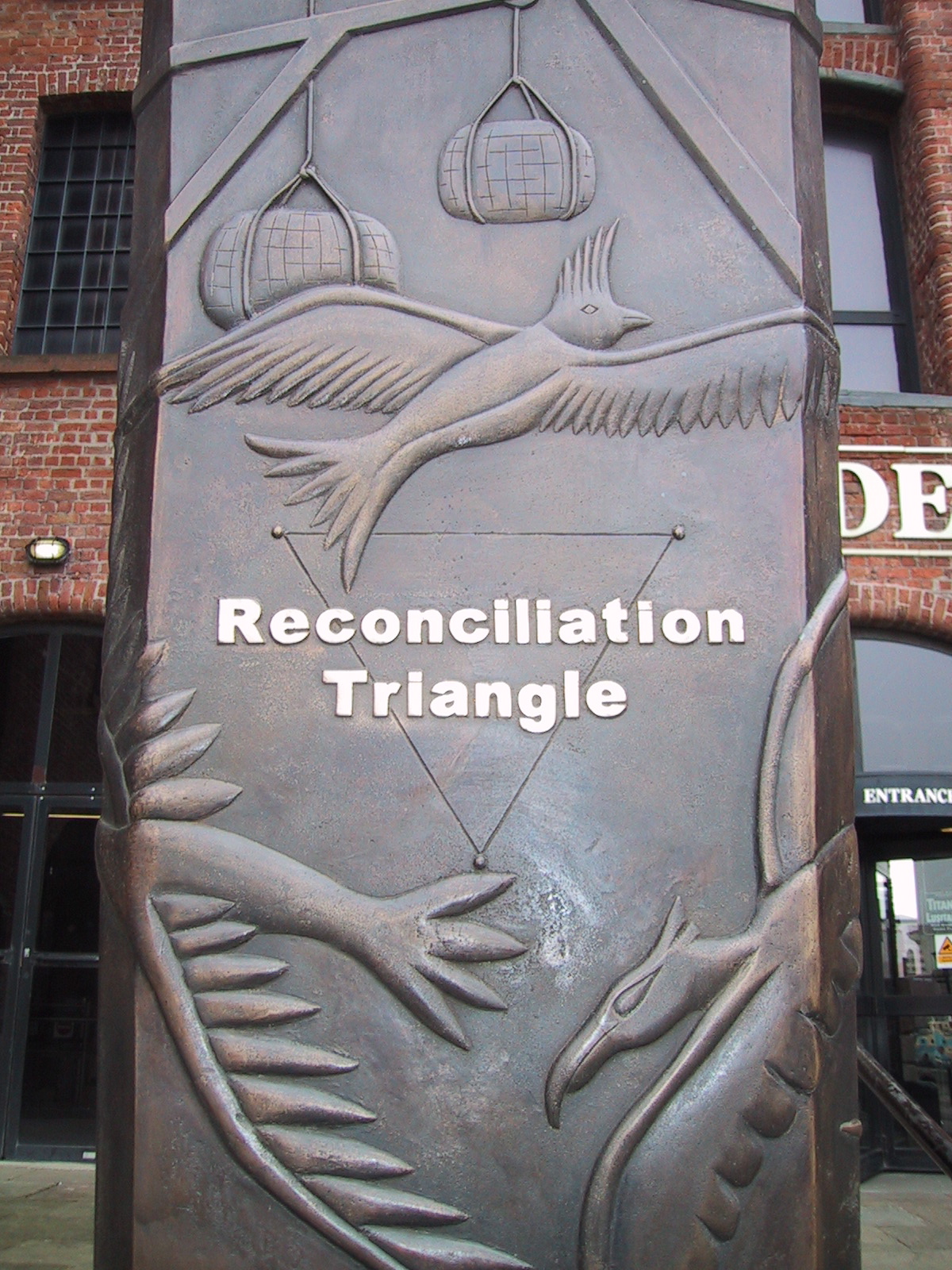

These new Reconciliation Triangle bronze sculptures are identical apart from the addition of bronze low-relief designs, reflecting images and thoughts on the slave trade and its effect on the peoples of Africa, the Americas and Europe.

The statue was placed at the Maritime Museum on the Albert Dock for a ceremony, before embarking on the journey to Benin.

Initial design work was undertaken by a group of young people in Liverpool, working closely with Garry Morris, the curator of the world famous Liverpool Maritime Museum Slavery Exhibition, and were completed by selected young people from Benin and Richmond. The final sculpture, based on the designs was finished with the help of sculptor Faith Bebbington. The sculptures were then cast in bronze and shipped to Benin and Richmond. It was intended that in Liverpool the bronze reliefs would be mounted and exhibited adjacent to the existing Reconciliation statue.

Liverpool Schools Students: Natasha Canning, Aron Walker of New Heys Comprehensive School, Jennifer Maudslay, Janine Butler of Holly Lodge Girls School, Michael Pinnington of St Margarets High School, John Fee, Abraham Okeya of Broadgreen High School, Zarah Baijeee, Letrice Thomas, Archbishop Blanch High School and Adam Boardman of St Edwards College.

Background

In December 1999, on the invitation of President Mathieu Kérékou of the Republic of Benin, an International Conference was held in Benin, attended by people from Africa, the Americas and Europe affected by the Black Diaspora, including representatives from Richmond, Virginia, and Liverpool. The President apologised for his country’s role in selling Africans to the slave traders.

On 9th December 1999, as its final act of the Millennium, Liverpool City Council unanimously passed a motion apologising for the city’s role in the Slave Trade, linked to a commitment to policies that would end racism and work to create a community where all were equally valued.

At the Benin Conference Lord Alton of Liverpool presented a small maquette of the large public sculpture ‘Reconciliation’ created by Liverpool artist, Stephen Broadbent, which already stands in Liverpool, Belfast and Glasgow along with a statement signed by the Liverpool’s Lord Mayor, Councillor Joe Devaney and the Leader of the Council, Mike Storey.

In April 2000 a ‘Ceremony of Racial Healing‘ attended by 4 Government Ministers from Benin, took place in Richmond, Virginia, U.S.A.

The intention was to extend this process of reconciliation, with encouragement at senior government level in Benin, it was decided to raise funds in the U.K. and Richmond Virginia to donate a 4 m high bronze edition of the ‘Reconciliation’ sculpture, with special additional designs by young people in Liverpool, Richmond and Benin.

The site for its erection was planned in a specially designed garden in the city of Cotonou in Benin. The President said that it would establish a meaningful international connection which would reflect the infamous slave triangle. The three statues would be a physical and symbolic manifestation of a process of bringing together in an expression of repentance, forgiveness and reconciliation – the descendants of those that profited from the evil trade, those on the continent from which they were taken and those now living in the place to which many slaves were taken.

Quotes

“Richmond, like the Phoenix, has emerged out of the rubble of racial hatred, the ashes of a civil war, and discord resulting from the enslavement of Africans. Over the last ten to twelve years, we have been led in the work of healing historical racial wounds. On behalf of our Slave Trail Commission, for the citizens of Richmond, and the people of the Americas, we will purchase and place this sculpture within a central location near the very place where the horror of slavery began in this country and as a monument to those who worked so diligently to end it.”

“Liverpool City Council expresses its shame and remorse for the city’s role in this trade in human misery. The City Council makes an unreserved apology for Liverpool’s involvement in the slave trade and its continued effects on the city’s Black Communities. The City Council hereby commits itself to work closely with all Liverpool’s communities and partners and with the peoples of those countries which have carried the burden of the slave trade.”

“The statue of two figures in a close embrace, by Liverpool artist Stephen Broadbent, is one of three identical monuments now in place at each point of the triangle. It stands at the heart of the business district, in a specially designed plaza. Water from a cascading fountain flows over a map of the slave triangle. An inscription describes the suffering of the millions of Africans who were transported from their homeland. It concludes, “Their forced labor laid the economic foundations of this nation.”

Ten years of coordinated efforts by Hope in the Cities teams in Richmond and Liverpool, working with both city governments, as well as visits to Benin, have played an essential role in facilitating the Reconciliation Triangle project. The Liverpool delegation spent several days in Richmond following the unveiling ceremony, to exchange experiences of honest conversation and trust building. Educators in public and private schools in Richmond hope that, by linking students with their peers in Benin and Liverpool, the Triangle can help to overcome one of slavery’s legacies – the prevailing racial and economic separation in the region’s schools.”

BENIN

“We owe it to ourselves never to forget those who are absent, but did not die their own death ... We must acknowledge our share of the responsibility in order to start afresh and pursue our goal towards progress. For us Africans this awareness opens the way to forgiveness and reconciliation.”

DETAILS

RICHMOND UNVEILING

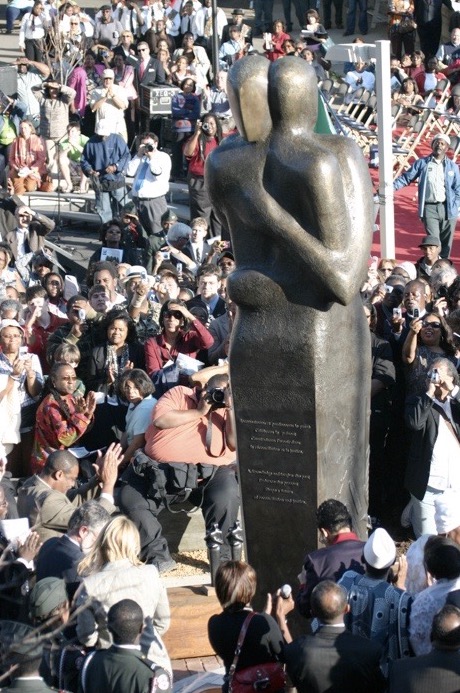

Five thousand people celebrated the unveiling of a Reconciliation statue on March 30 at the site of Richmond’s former slave market. In this place of horror, where 300,000 kidnapped Africans and their descendants were torn from their families and “sold down the river” to Southern plantations, a symbol of healing gives hope for a new future.

The Ambassador of Benin called it “a blessed completion” of a triangle of new relationships between Benin, Richmond, and Liverpool, UK – each of which had profited hugely from the traffic in human flesh.

“Our ancestors longed and prayed for this day,” said Rev. Benjamin Campbell, whose vision led to Richmond’s first “walk through history” organized by Hope in the Cities [2] in 1993, and the marking of sites on the historic Slave Trail. He opened the event by welcoming everyone in the name of the Powhatan people, on whose land the city was built, the European settlers, the hundreds of thousands brought from Africa into bondage, the prophets of freedom, and those who had repented for the sins of racism.

Governor Timothy Kaine told the crowd that the resolution of “profound regret” by the state’s General Assembly in February was appropriate, since Virginia had “promoted… defended… and fought to preserve” slavery. In his keynote address, Dr.John Kinney, dean of the school of theology at Virginia Union University, said racial reconciliation, like surgery, carries a degree of risk. But it also offers the prospect of eliminating the pain of past and present generations and opening the way to a new future. He challenged the crowd, “Today is not a conclusion. Today is a day of commitment.”

Delores McQuinn, vice president of Richmond City Council, and chair of the Slave Trail Commission, recalled her enslaved great-grandfather. When his son asked to see the records of his family, the plantation owner burned them before his eyes. “If I stand here today, I cannot be a hypocrite,“ said McQuinn. “ I too must extend forgiveness from the depth of my heart and soul.”

Kim Johnson, diversity manager for Liverpool City Council, led a delegation of fifteen, representing local government, education and community organizations. On behalf of the Lord Mayor, she presented a framed copy of the city council’s 1999 apology for its leading role in the slave trade. She called for open and honest dialogue. “Only by taking personal responsibility will we bring about lasting change.”

Ambassador Segbe Cyrille Oguin of Benin told how in 1999 President Kerekou had launched a program of reconciliation between Africa, Europe and America by apologizing for his country’s role in selling fellow Africans. The following year he sent a delegation to Richmond to repeat the apology. “The Republic of Benin, that was unfortunately involved in those shameful deeds, is now here, taking part in this duty of memory, and the noble desire to restore our broken-down relationships,” said the ambassador. The ambassadors of the Gambia, Niger and Sierra Leone were also present at the unveiling.

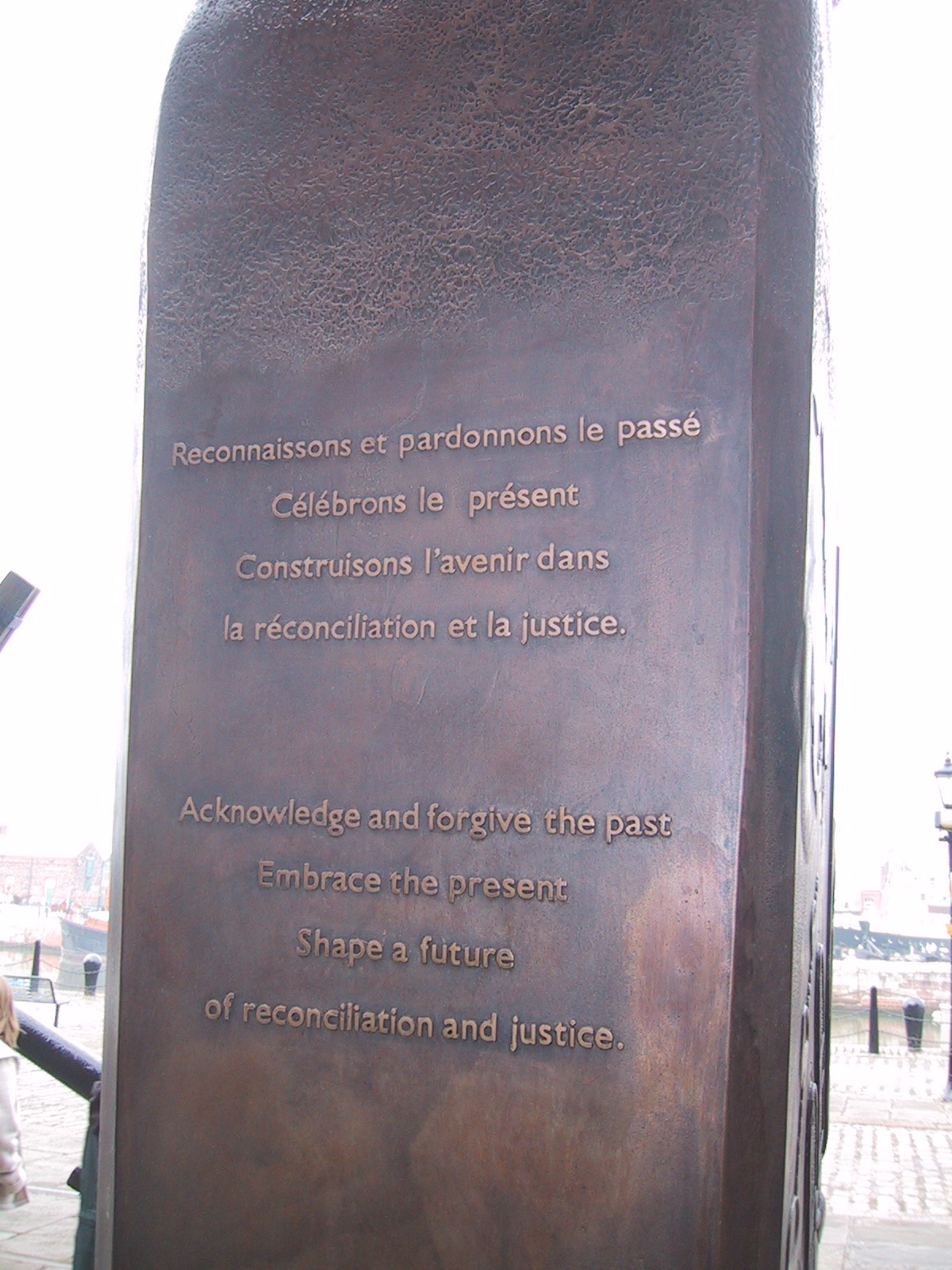

Audrey Brown Burton, one of Richmond’s pioneers for racial healing said afterwards, “I saw something I thought would never happen in this city.” An inscription on the base of the sculpture, composed by Richmond school students, reads, “Acknowledge the past, embrace the present, shape a future of reconciliation and justice.” The Richmond Times-Dispatch headlined its front page story, “A monument to reconciliation.”